While Putin denies the existence of the Ukrainian nation, the country’s rich folk culture proves otherwise, argues Katya Zabelski.

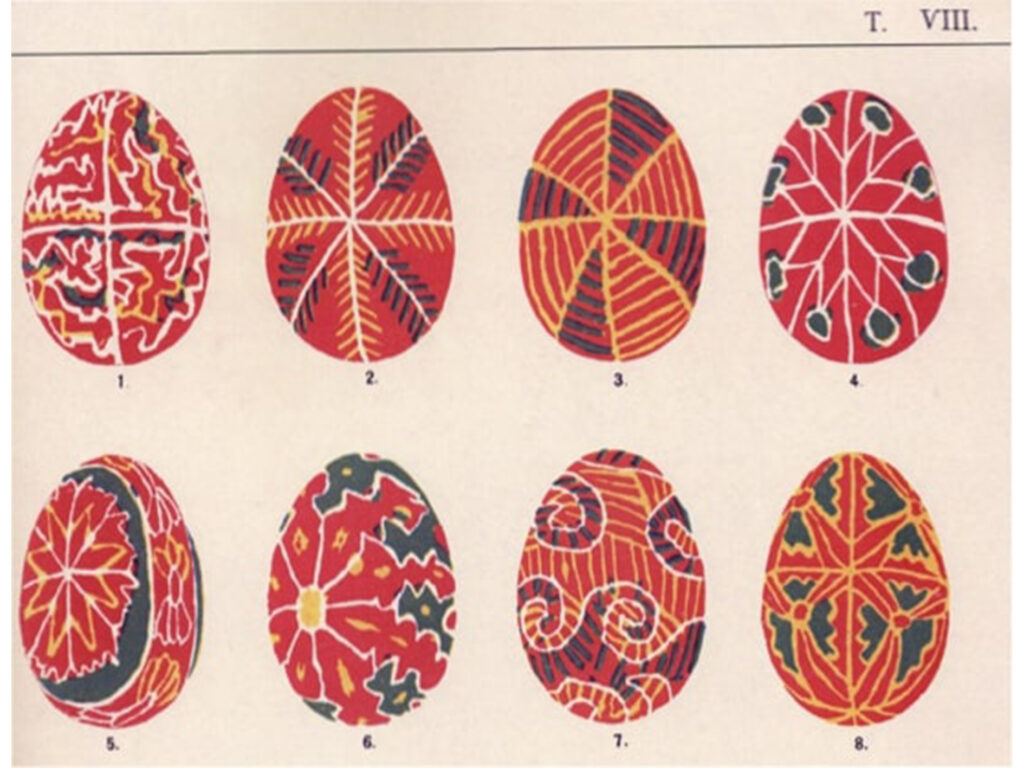

About a week ago, Putin started his full-scale invasion of Ukraine. What’s been following for me personally, are nights filled with nightmares, mornings filled with dread, and endless scrolling. This morning, I read news of another civilian flat hit by a missile. These homes are a 10-minute walk away from my mother’s flat, where she grew up, where she attended university and where my grandparents fell in love and grew old together. Videos of citizens taking up arms, men saying goodbye to their families, babies being born in bomb shelters flood social media and it feels like all I can do is watch. Although it feels like a lifetime ago, I was writing my dissertation roughly this time last year. Originally, I wanted to analyse how Ukrainian folk art symbols were used throughout Soviet-era propaganda to influence the Ukrainian peasant class. As I started doing research, I unravelled this deeply complex, convoluted, and undiscovered world of Ukrainian folk art. This was an extremely difficult topic to dive into, particularly as resources and materials were hard to come by; which only highlighted to me the ongoing effects of repressed and underrepresented culture and how this fed into public, political and social consciousness of a nation. I realized that this dissertation was an opportunity for me to not only bring attention to Ukraine but to paint a bigger, political, and national picture through art. I first thought that Ukrainian folk art had just been appropriated, but I soon realized it had been romanticized, misunderstood, neglected, and used as a tool for political resistance and national pride. And now, more than ever, Ukrainian folk art is under attack. I can’t help but think back to my case studies throughout my dissertation and how revealing they are of today’s conflict. Ukrainian folk art symbols, such as pysanky egg painting and vyshyvankas, first went through the process of romanticizing in Imperial Russia.

Russia sought to expand its empire and place itself on the world stage with a strong national identity. However, collective identity was lacking. In National Bolshevism, David Brandenberger investigates how the first census prepared by ethnographers found that peasants did not distinguish between Belorussians, Great Russians or Ukrainians, and instead, relied on more tangible regional identities or addressed themselves in relation to their names, like “Vladimirians” and “Kostromians.” Imperial Russia utilized Ukrainian folk art to help convince the world of its “togetherness,” putting crafts like petrivikya painting, which can be traced back to the village of Petrykivka in Dnipropetrovsk oblast of Ukraine, in exhibitions and circulating throughout the economy. Ukrainian folk art was used to build a unified Russian imperial identity. This swallowing of other cultures through the justification of homogenous language and culture is still seen today through Putin’s claim that Russian speakers in Ukraine are under attack and need to be protected. As Imperial Russia began participating in exhibitions like the 1900 Paris Universelle exhibition, practices and regional differences within Ukrainian folk art were recontextualized and reorganized as “Russian folk art.”

By saturating foreign markets with products decorated with folk art motifs and symbols, Russia was able to appear modern and economically engaged, while also preserving a “unique” visual tradition. As these folk art practices became more popular, they were also strategically made more marketable and “refined” to adapt to elite tastes. Gentry women throughout Russia started creating workshops with the goal of reviving folk arts (particularly because they saw folk art as a woman’s art form that needed to be upheld.) Some argue that these workshops were a beneficial arrangement for both parties, as these initiatives kept the peasant crafts alive while employing peasant women. However, Walter Benjamin critiqued the process of art becoming involved in the process of reproduction, claiming that ‘the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition… lead(ing) to a tremendous shattering of tradition which is the obverse of the contemporary crisis and renewal of mankind.’ As soon as an artwork begins any process of reproduction, it also begins to lose the uniqueness that ties it with the fabric of tradition that it came from. In this attempt to reproduce, there is a loss of appreciation and understanding of how these objects and arts were used in real people’s lives.

How Ukrainian folk art became engrained in Russian art and culture provides unique and much-needed context for why so many Russians (Putin included), claim that Ukraine is “not real” and merely a part of Russia. The effects of imperial ideologies which appropriate and mould other narratives and cultures for their own imperial agenda can still be seen today. After their romanticization, Ukrainian folk art symbols were further manipulated, this time within Soviet propaganda. Stalin needed to mobilize the Ukrainian peasant population in order to have a successful mass collectivization campaign as the number of rural residents was four times that of urban residents. By convincing the large Ukrainian peasant population to abandon individual farming, Stalin could complete a socialist transformation of the agrarian sector and support himself, his exports and his growing industrial workforce financially.

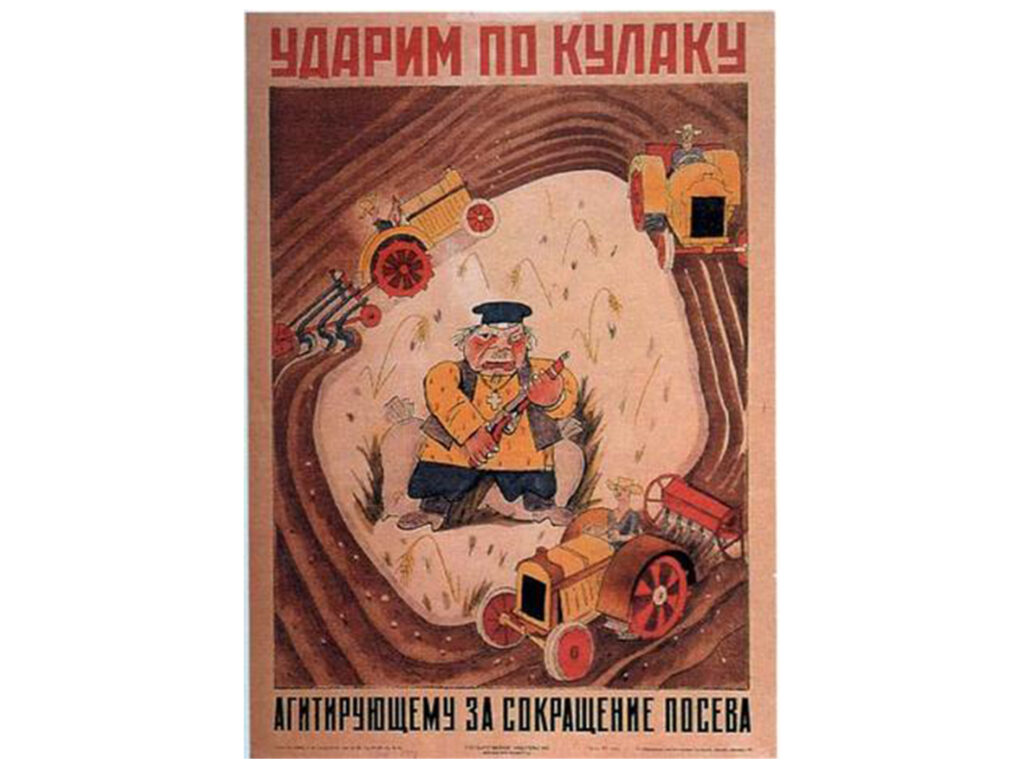

To weaken the peasant populations, class distinctions within villages were introduced. The state made the demonization and elimination of the “kulak,” or wealthy peasant, an issue of primary importance. These class separations within the peasant community were purposeful; authorities knew they would lead to disruption and conflict, making the peasant communities easier to control. Kulaks in Soviet propaganda posters were easily identifiable and had a cohesive visual identity. He was often overweight (implying his greed) and often old (implying his outdatedness and unproductive nature, making him unhelpful to the State). In one example, the kulak character is separated from other peasants through his clothes. He is usually depicted wearing a vyshyvanka, a traditional embroidered Ukrainian shirt, while the other figures have on other generic peasant clothing. In this case, Ukrainian folk art and motifs, like embroidered clothing, were used to highlight who the “enemy of the state” was.

This demonization of Ukrainians continues and is spewed throughout Russian state media, fuelling Putin’s disinformation about the Ukrainian people and their “Nazi” politicians. What is often most interesting about folk art is that despite its reputation as representing the past, it is continually changing, fluid and relevant. With the resurgence of national pride in Ukrainian identity, folk art motifs have experienced a renaissance and are now utilised as a tool to unite communities against oppressive political forces. The patterns of misuse and suppression that have created a historical past through Ukrainian folk art symbols are flipped and reappropriated to strengthen a resistant national identity. The Ukrainian folk art symbols are thus used to resist the common historical narrative of oppression and appropriation and instead used to create a sense of historic continuity through resistance.

I explored some of the contemporary art that was created with and throughout the Euromaidan resistance, including a cut out of St. Nicholas and the Creche. This piece, made by an artist’s collective from Lviv, sought to bring in a ‘naive, ethnic, home-brewed element into the place of the occupation.’ The reclamation of the religious symbol and its original function resists Soviet atheistic politics which led to the elimination of many traditions, such as the creche, from Ukraine. It showcases the way that folk imagery is used as a tool of resistance and reclamation, strengthening a resistant national identity and providing a source of connection. It is not only the explicit art pieces erected during the Maidan protests that utilised folk symbols as a form of resistance. Many people at the Maidan protests wore pieces of traditional Ukrainian clothing, such as vinoks and vyshyvankas. Comparing modern photographs of Ukrainian protesters in vyshyvankas with the caricatures of the kulak peasants in the Soviet propaganda posters highlights this reclamation of Ukrainian folk tradition through clothing.

The importance of national folk art and history should not be discredited. National histories attribute to methods of self-identification, legitimization, political expression, and civic upbringing. There is, of course, a danger in putting too high of an importance on national history. It can lead to exclusion of ethnic minorities, immigrants, or formerly colonised people that do not feel like they fit neatly in any national history. It can lead to dangerous political action or be used as a justification for nationalist, right-wing movements. However, national history through folk art can also be a beautiful tool that gives people a sense of identity, a sense of shared connection. The ultimate goal of my dissertation was to humanize the people of Ukraine and showcase the validity of Ukrainian national identity through art. Many people have marvelled at the Ukrainian people’s ability to come together in unity during a time of crisis. I think, looking historically through the lens of art, people feel they have to. Ukrainian people, their culture and their identity has been historically under threat and they see this as their final chance to save it. This is their final chance (with the world watching this time) to show that Ukrainian people, history, sovereignty, and culture, matter.

Katya Zabelski recently graduated from the University of Edinburgh with an undergraduate degree in Art History. Katya is the co-editor in chief at Radical in Progress (an educational website that focuses on providing free and accessible study guides on social justice literature) and is an editor for Project Myopia (a website devoted to diversifying university curricula through crowdsourcing material from students.

PLEASE DONATE here if you wish to support and help protect archival materials at Central State Historical Archive of Ukraine in Lviv. Thank you!