Drifting between 90s and Aughts nostalgia and techno-futuristic escapism, the Super Bowl ads are a powerful seismograph of our age’s collective vibes.

One of the things that makes high-level competition compelling – beyond simply watching people at the top of their game playing it – is the narrative that often gets associated with big games, important players, rivalries that go back through the decades. And the Super Bowl, and NFL playoffs more generally, are full of narrative, something that feels impacted by the fact that the post-season in the NFL is all single elimination (as opposed to a series in something like baseball): every team has something to prove, and small mistakes have big impacts. The narrative around Super Bowl LVI was a classic of underdog vs the favourite; the upstart Bengals, going from winning their first playoff game in decades to the Super Bowl, against the LA Rams, a team that includes the best player in the NFL (Aaron Donald), and with Matt Stafford at quarterback, have their own narrative at play: can Stafford, after toiling for years with bad teams in Detroit, finally get a ring when there’s a better group of players around him.

And while all of this is compelling in and of itself, everything else that surrounds the Super Bowl: the halftime show, the strange obsession with advertising that the commercials create, are able to create narratives themselves. But these narratives have nothing at all to do with sport, and instead, have everything to do with the culture that surrounds them. It makes sense that the Super Bowl, the biggest game of the year in the NFL, and a single-elimination one at that, would be something that creates a feeling of being singular. And the cultural output that surrounds it feels the same; the halftime show and commercials capture where culture is in the moment; what’s compelling to people, what’s selling, what people want from the world around them.

The biggest and clearest example of this is the halftime show, and this year’s captures something that echoes through into the commercials too. By bringing together so many different big names to perform – Dr. Dre; Snoop Dogg; Mary J. Blige; 50 Cent; Eminem; Kendrick Lamar; and even a small cameo by Anderson Paak during ‘Lose Yourself’ – feels like a distillation of what might best be described as cultural maximalism: productions needing to be bigger, crossovers becoming more ambitious, scale being ramped up and up and up. It feels like the next step after the seismic box office performance of a film like Spider-Man: No Way Home, which, in the eyes of fans, lived and died by the extent to which it integrated heroes and villains from different universes, a multiversal continuation of the team-up that defined the Avengers films.

Beyond this, one of the common ways that this halftime show was defined was through the lens of nostalgia; from 50 Cent opening his performance of ‘In Da Club’ upside down, a callback to the music video from 2003; and responses from all over Twitter referencing the fact that this show was made with generation X and millennials in mind. Alongside this move towards the recent past, and the rose-tinted glasses that it might be looked at through, it existed in tension with a very specific and contemporary moment. Eminem took the knee during ‘Lose Yourself,’ a gesture of solidarity that’s had a thorny relationship with the establishment of the NFL. There were even stories that he was told not to take the knee, even though, after the fact, a league spokesman acknowledged the fact that everyone was aware that Eminem would engage in that gesture of solidarity and protest. A protest signed off by the establishment is an interesting idea; does it work as protest, is it a sign of something charged and political becoming commodified?

Commodity is the order of the day when it comes to Super Bowl commercials; the products often feel like an afterthought compared to the sheer volume of big names and cultural icons that appear in these short TV spots. The ad for Uber Eats leans on the fact that they now deliver more than just food, and big names like Jennifer Coolidge and Nicholas Braun are shown eating everything from packaging to paper since they don’t know what food is anymore. But the strangest moment is Gwyneth Paltrow taking a bite from a Goop candle, with all that that entails. This feels less like a way of advertising Uber Eats, but more a way of selling the personas of the celebrities in the ad itself. It’s no wonder that so many of them leaned on nostalgia, reaching even further back into a shared cultural history than the halftime show itself; Jim Carey reprises his role as the Cable Guy; the villains from Austin Powers reunite; Zac Braff and Donald Faison, who first appeared in Scrubs together over twenty years ago, are in an ad together. These pairings and reprises lean heavily on the fact that what’s compelling to people now is nostalgia; the comfort of the past (something that may feel even more pronounced after the challenges and upheavals of the last few years), a warm embrace from things that you once loved, and might, in that wistful way, love still. The end of the first season of Mad Men sees Don Draper selling a Kodak Carousel by tapping into nostalgia, what he describes as “a twinge in your heart far more powerful than memory alone.” Like the Carousel, these ads aren’t designed to be spaceships – even if one, starring Matthew McConaughey, plays like a trailer for an Interstellar sequel – but time machines.

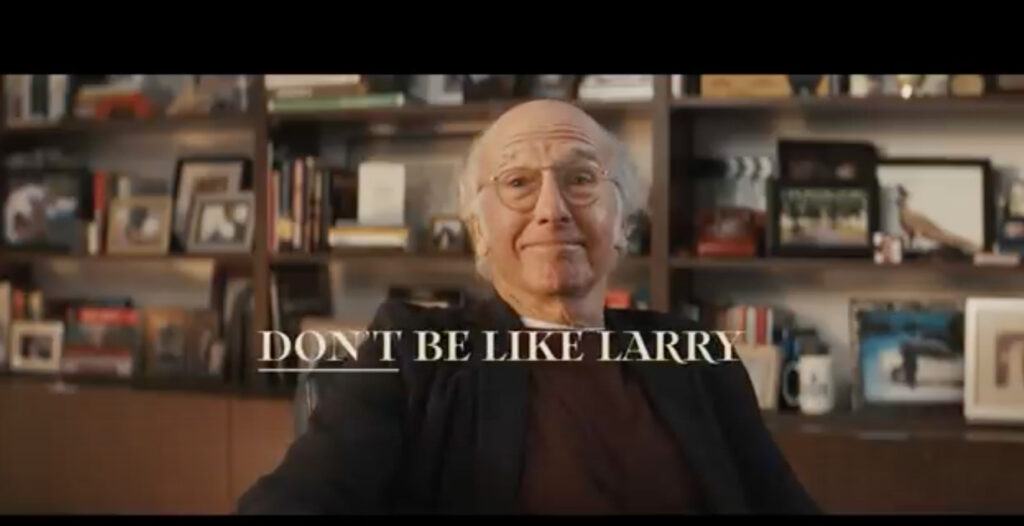

In spite of this, one of the defining factors of the Super Bowl ads was crypto, from enigmatic QR codes to a nay-saying Larry David moving through history, the biggest stage of the year for advertising is trying to make inroads into something new. This tension feels like it’s at the heart of both the halftime show and the commercials, the narrative of our culture caught somewhere between a strange future that’s being sold to us – one defined by virtual reality and crypto, seeming to sidestep what a future rooted in the physical world might look like – all while it remains haunted by the ghosts of the early 21st century. The branding on display here isn’t just done by corporations, but by the figures that appear in them; the reason that Larry David in a crypto ad will theoretically “work” is rooted in the ways in which people understand Larry David: as the world-weary protagonist of Curb Your Enthusiasm, as the man who would be George Costanza in Seinfeld. He’s a kind of archetypal version of the “old man yells at cloud” joke in The Simpsons; at once being used for his curmudgeonly presence, and for the idea of crypto providing the shock of the new, an attempt to speak to more sceptical generations through one of their own mouthpieces.

The narrative of the Super Bowl itself resolves when the game is over; in this case, the “better team” won, the best player in the NFL received a Super Bowl ring, and Stafford was able to prove that, with the right squad around him, he could be as good as he needed to be. What’s interesting about the narrative(s) created by everything surrounding the game itself, is that there’s no sense of resolution here; even something more contained like a single (group) performance, as opposed to charting a course through a bunch of minute-long ads, seems to leave everything up in the air; from the maybe-maybe-not manufactured tension around Eminem taking the knee, to the uneasy relationship that’s tried to be created through nostalgia and a brave new world, the idea of what that world might look like remains unclear. This cultural narrative works precisely because it’s so uncertain; everything is caught between the easy comfort of the past, and the uncertainty of a world that won’t stop changing. To offer a resolution to this fundamental tension would be to misunderstand the strange, non-place that the culture is in. The ad for Uber Eats argues that because they deliver more than food, people don’t know what they can eat anymore. It feels like a microcosm of the moment; what’s the past or the future, what’s new or a rehash, it all seems uncertain. Even as these ads and their audiences continue to look back; on formative films, comfortable sitcoms, hip-hop from a decade ago or more, the question of what they’re looking for remains unanswered.

Sam is a writer, and one of the founding editors of Third Way Press. Their writing on culture and identity has been published by Frieze, the LA Review of Books, Neotext, and other places. They have written two books, All my teachers died of AIDS (Pilot Press, 2020), and Long live the new flesh (Polari Press, 2022).