Charles Bukowski wrote for people who were as addicted, disillusioned and outside of society as himself, creating tales of total burn-out in the ‘Golden Age of Capitalism’. Yet, in the past decade his writings have become associated with misogyny and the politics of the Far-Right. How should we consume his work? And should we even bother?

‘History makes, history unmakes, the novel.’ This was Irving Howe – a prominent New York literary theorist – writing in 1990. For Howe, the novel was never simply a random assortment of words, an innocuous plaything; rather, it was shaped by a specific historical context and politics – say, the French Revolution, or the First World War. It was ideological from the moment the author put pen to paper because it was bound by this context. Howe fretted about the flow of time, contending that as decades and centuries flash by, the novel is confronted by new value-systems, contexts and politics; it becomes an anachronism. He was disturbed by this process, by the inevitability of it.

In the essay in question – ‘History and the Novel’ – Howe makes particular reference to the work of Jane Austen and her third novel, Mansfield Park. It is heavily implied in the novel that Sir Thomas, a wealthy landowner, owns slaves in the Caribbean, a point many critics have taken as evidence of Austen’s complicity in British colonial violence. The novel thus becomes politicised in the present – reading it generates questions of power, historical questions of race and injustice. Literature becomes the battleground for the politics of identity so familiar to us today: the politics of Brexit and multiculturalism, of Donald Trump and ‘cancel culture’, of alt-right extremism, etc.

Another example: in 2013, Timothy McNair, a black student at Northwestern University in Illinois, snubbed Walt Whitman – ‘America’s poet’ – on the basis that he upheld discriminatory racial stereotypes. What we have here is the privileging of the now to correct the mistakes of the past. Calls to ‘decolonise the curriculum’ come from a similar interpretive angle. In English Literature courses, this manifests as a diversification of the literary canon – a good thing, no doubt, in any liberal democracy. But what is the dividing line here? Do we jettison Whitman and Austen entirely because they lived and absorbed an outmoded cultural politics?

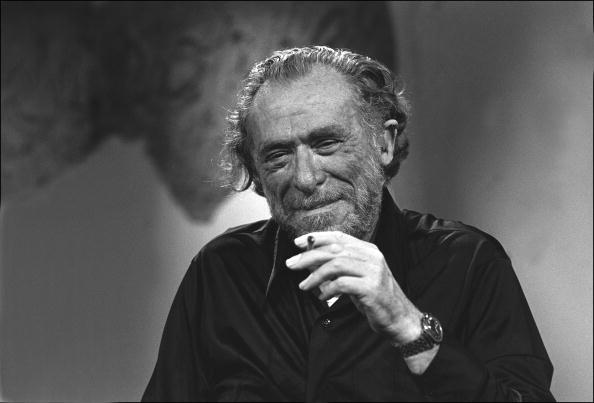

Charles Bukowski sits awkwardly in these debates. Born in Germany in 1920, Bukowski nevertheless spent most of his life in Los Angeles, moving between dead-end jobs, drinking, and generally trying to subsist. His ‘break’ came in 1969 when his publisher at Black Sparrow Press encouraged him to take up full-time writing. He had always written. It was never ‘literary’ – indeed, his appeal was defined precisely by this lack of pretension. He wrote in simple prose, of simple experiences – drinking, gambling, sex, work. He was of the Beat Generation: an outsider, unflinchingly honest, unpretentious. He spoke for the down-trodden. The context to his writing is important too: beaten as a child by his father and disfigured as a teenager by horrific boils, Bukowski was exposed to cruelty and rejection from the beginning. Perhaps the tragedy of his youth explains his philosophy: simply, ‘I don’t like people’.

But he is important to consider here because he is extreme. In August 2020 he featured in a US journalist’s viral tweet taking aim at the ‘top 7 warning signs’ on a man’s bookshelf. The charges are by now well-known: he is widely castigated as a misogynist, a narcissist, and an abusive alcoholic. He exemplifies a mode of thinking now denounced by Western liberal intellectuals: an old twentieth-century political consciousness, ignorant, if not downright dismissive, of social injustices related to gender, race, and sexuality.

More worryingly, he is deified in online alt-right circles with an intensity matched only by the hatred of his critics. Incels – a growing sub-culture of mostly young white men for whom sexual failure constitutes their entire lived identity – feel validated by Bukowski’s casual misogyny; when he begins his novel Women by reflecting on four years of (involuntary) celibacy, incels know this to be a profound social violence, undermining his virility, his identity, his very humanity. For the Right, his novels in effect, have become twenty-first-century manifestos of misogynistic self-assertion.

Decades after his death, Bukowski, therefore, finds himself, caught in the middle of a cultural tug of war. He has been politicised beyond measure. When we read him today, we are unwittingly entering into this arena. A friend who sees us reading him may raise an eyebrow; worse yet, they may accuse us of being ‘part of the problem’. He raises questions about our values, our politics, even our decency as human beings. And, where Bukowski is concerned, we cannot simply ‘make discounts . . . for an earlier time’, as Howe puts it. Even as he wrote Post Office in 1969, countercultural, progressive energies were spreading on a global scale. Bukowski’s views toward women were already outdated fifty years ago.

But that’s the thing with Bukowski: he is so much more than this caricature. In this polarising culture, his writing is reduced to misogyny, narcissism, and abuse – by both sides. This doesn’t explain the scores of admirers he has fostered, many of whom aren’t – to my knowledge – reading him as a guide to morality. The critical questions then are these: why do we read him in the twenty-first century? Should we read him at all?

The answer is yes, but only if we change our lens of focus away from these divisive cultural issues. Admittedly, this is made difficult by Bukowski’s obsessive preoccupation with women – the subject of an entire novel. But recognising him as problematic should not diminish his value to readers, as it shouldn’t for Austen or Whitman either.

Take Factotum, his second novel, published in 1975. At its heart, the novel is a rumination on the meaninglessness of work. Factotum – literally meaning ‘an employee who does all kinds of work’ – follows Bukowski’s semi-autobiographical alter ego Henry Chinaski as he plods his way through low-life 1940s America. Bukowski captures that modern sense of unease specific to young adults: what to make of yourself? He is cripplingly poor; in one scene he comically fails to steal a cucumber for his dinner. Bukowski takes aim at capitalism in a fairly radical way:

“How in the hell could a man enjoy being awakened at 6:30 a.m. by an alarm clock, leap out of bed, dress, force-feed, shit, piss, brush teeth and hair, and fight traffic to get to a place where essentially you made lots of money for somebody else and were asked to be grateful for the opportunity to do so?”

The novel is so repetitious it becomes by the end almost disorientating; it evokes a particular sense of dread as each job follows the last inexorably: shipping clerk, warehouseman, cleaner, and so on. His critique is economic, material. It is the kind of critique missing from today’s political discourse, consumed as it is with the politics of identity.

Bukowski inhabited the ‘golden age of capitalism’ – from the end of the Second World War up until the mid-1970s – and still found it sorely lacking. Since then, job dissatisfaction has only intensified. David Graeber, in 2013, criticised this proliferation of ‘bullshit jobs’: ‘How can one even begin to speak of dignity in labour when one secretly feels one’s job should not exist? How can it not create a sense of deep rage and resentment?’Nor is this some abstract theory on his part: YouGov data in 2020 highlighted that as many as 26% of UK workers feel dissatisfied in their job. The figure is higher for those in manual industries. Bukowski captures this feeling of dissatisfaction better than anyone. When ordered to shine a brass railing of the Times Building in LA, he reflects that ‘I’d had dull stupid jobs but this appeared to be the dullest and most stupid one of them all.’

But, in the same breath, he mocks any serious political engagement, any transgressive ambitions. In Ham on Rye (1982), he plays a Nazi at school just for the shock of it; in truth, he cared for ‘neither the Nazis nor the Communists nor the Americans.’ His writing was characterised then by a strange duality: critique without any notion, or desire, for change. In the rat race that is modern existence, Bukowski was a resigned, disillusioned participant. He evokes the depoliticised figure of today; that individual identified by Mark Fisher, for whom capitalism is no longer an economic mode of organisation, but a natural and inevitable fact of life.

It’s also easy to romanticise Bukowski. He embodied a kind of liberal work ethic in his writing: a belief in hard work and self-discipline. He wrote incessantly, and ultimately reaped the rewards of that perseverance. Certainly, this is a lesson you can take from him: that rags-to-riches tale embodied in the American Dream. But it’s a very distorted version: one which ends where it started, with the dependency of drink.

This is also why we should read him. Bukowski is not idealistic; he deals with malaise as any normal person does: not with political activism, but with beer and liquor. Even he realises this hedonistic escapism is destructive, but it shields him from the reality of the world as it is, a world devoid of meaning and community. And that is, perhaps, one thing both the Left and Right can agree on. From Hayek and Fukuyama to Fromm and Fisher, a critical question has united the yawning gap between their philosophies: are we fulfilled in the economic conditions of capitalism, with its free markets, its rampant consumerism, its American Dream?

The thing to understand about Bukowski is that he still resonates; time has not diminished him because he writes of twenty-first-century issues: the meaninglessness in work, the hopelessness of political radicalism, the allure of hedonism. None of this is to be admired; rather, it speaks to us as the world really is, or at least as many perceive it to be. Awkward though his presence in twenty-first-century culture is, one thing is clear: history has not unmade Charles Bukowski yet.