How one of the most beautiful parks in Ukraine’s capital is changing its face with the war and is becoming a memory to the dead.

The Hryshko National Botanic Garden slopes down the western bank of the Dnipro River in the heart of Kyiv. When the line of trees dips with the incline of the earth you can see Ukraine’s great river winding through the capital city on its long journey to the Black Sea, flanked by bridges and domed churches.

I am greeted by Olena from Peli Can Live, a Ukrainian NGO which is developing an irrigation system for the garden and running a campaign to keep its greenhouses heated through the upcoming winter, when Kyiv is expected to suffer power-cuts under Russian bombardment. She tells me that the garden helped to calm her mind amidst the stresses of the war, or when she worried about her friends in Russian occupied territory and the threat of air strikes.

Despite its location in the heart of Kyiv, the sprawling capital city is largely hidden from view in the garden, giving a visitor the impression of being in the midst of a boundless forest deep in the past. The greenery provides a sanctuary for biodiversity, including birds and wildlife such as the red squirrels which have all but disappeared from my homeland. The garden hosts a collection of rare plant-life and species from around the world which can be studied by scientists such as Yuri Klymenko the Head of the dendrology department in the Botanic Garden. who has worked in the garden for over four decades.

Olena and I are far from the first to acknowledge the calming and regenerative properties of this green oasis. We come across the graves of monks who meditated here and a woman on her way to pray. There is a church in the centre of the garden and another snuggled at its feet by the river named St Michael’s Monastery; this one older even than the Mongol invasion of 1241 — it reaches as far back as the 10th century, Yuri says. He goes on to tell of how when Volodymyr converted to Christianity in 988, he ordered the idols of the land’s pagan gods to be cut down and thrown in the river where the city’s inhabitants were then baptised en masse. When one of the idols washed up on the riverbank, Volodymyr built the Christian monastery so as to prevent people from worshipping their old god there.

Following the path there is a viewpoint that looks down upon the church, focussing it as the centrepiece between two forested slopes backgrounded by the Dnipro; a deliberate design, according to Yuri. When the garden was conceived under the Soviets, it was unsafe to have the main point of composition be the dome of a church because of communism’s antagonism to organised religion – anything related to religion was prohibited.

“But Leonid Rubtsov, the founder of the Dendrarium in the Botanical Garden didn’t care, he said I want to do it and he did it. Now it is even hard to explain why, what was wrong with that.”

As the team dug trenches for the new irrigation system they found traces of a king’s palace from the tenth century, where the ruler would have enjoyed easily defensible high ground and good hunting. “It was the tenth century, because in 966 another king attacked this territory and destroyed everything here,” Yuri explains. Evidently, the conservation of space for nature has the happy corollary of also conserving a rich history.

The Irrigation Project

The ‘Water for Botanic Garden’ irrigation project is vital to conserving and expanding the variety of existing plant species in the garden. Rising temperatures in summer causes drought, which weakens the trees’ ability to defend themselves against diseases and insects like a tired immune system. This in turn exacerbates the spread of disease. Most of the ash trees here are already dead from the same disease which has wiped out much of the species in the UK and across Europe. As climate change increases the likelihood of higher temperatures, more species are at risk of being decimated across the continent and beyond as diseases proliferate. Many trees in the garden are darkened, leafless or dying, especially in areas without the irrigation system. July was the world’s hottest month since records began in 1850, and 2023 as a year is likely to break a similar record.

They would have had to give up on some trees or pay for trucks to deliver water, Yuri explains. Now, with the irrigation system, they can provide water to areas automatically or with the flick of a switch, which is a more sustainable, efficient, and cost-effective solution. They have only completed a fraction of the planned irrigation system in the garden, and you can already see the lush results of hydration despite the intense July heat. The more irrigation they have, the more Yuri and his colleagues can “plant shrubs and other trees because we can water them… they won’t survive if they have no water.”

Alley of Heroes

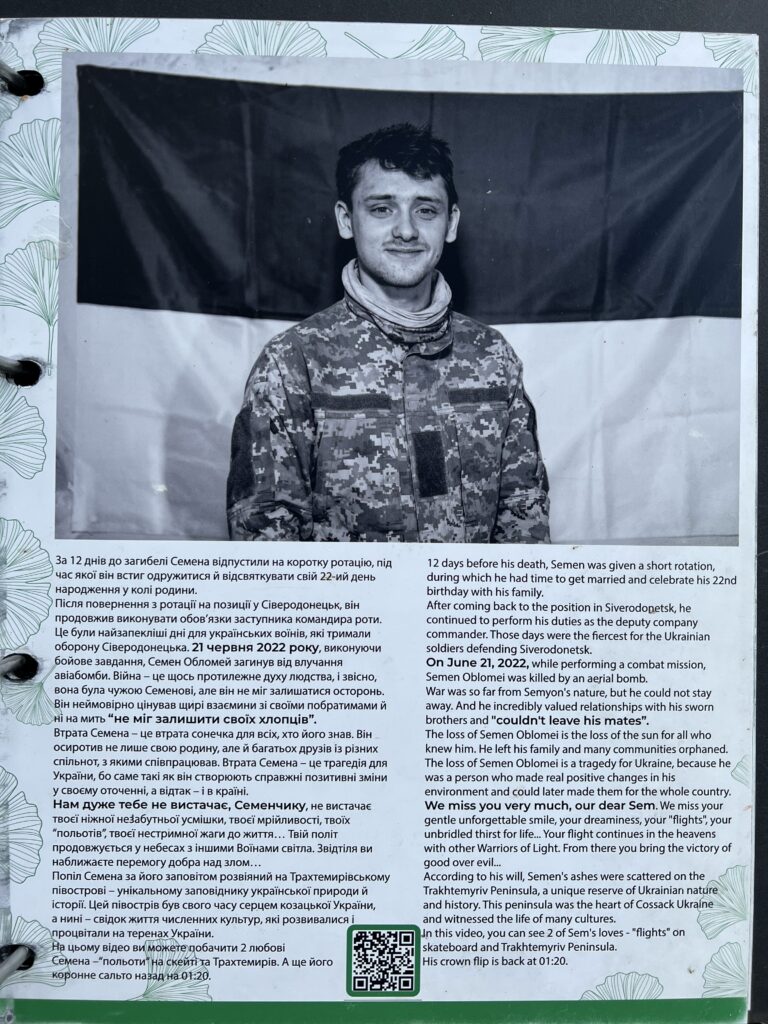

One species of endangered tree found here is called the Gingko, which is as ancient as the dinosaurs. In a small clearing a little way off the path we find a Gingko dedicated to an erstwhile volunteer named Semen Oblomei, an aspiring young arborist and environmental activist with the Peli Can Live team.

“He was 22,” Yuri says, and sighs deeply as Olena repeats his words in translation. “He really liked these trees, Gingko, and he found the seed, planted it and said, when it will grow I will plant it here. But he died, so his family did it.”

When Putin invaded, Semen signed up to the army and was killed in an aerial strike in a few months later. The Semen Oblomei Foundation was set up in his memory and seeks to provide specialised arborist education within Ukraine, something currently lacking.

Pointing to a grey circle in the nearby grass, Yuri jokes:

“It’s not a mine, it’s the irrigation system.”

Semen is not the only casualty of war memorialised by a new life in the garden. A student organisation has set out an ‘Alley of Heroes’ on a pathway which overlooks St Michael’s Monastery and the Dnipro River. Along the pathway are placards signposting saplings planted in honour of fallen students; so far there are five. Most of the birthdates are from the late nineties, all of the death dates are since February 2022. As a place of natural beauty imbued with historical and spiritual significance, the garden continues to be invested with meaning by the community and now contributes to remembering lives lost in the war.

Like Semen, many of the garden’s employees have gone to fight, and the government has tightened the budget (prioritising funds for the war) so Yuri can’t afford to hire new employees. Meanwhile, months of closure crippled the garden’s usual source of income. Fortunately, ordinary Ukrainians have stepped up to the task. At the outbreak of war nearly everyone became a volunteer of some kind — Olena, then working in publishing, printed academic textbooks to donate to students-become-soldiers, for example — and thousands of locals have come to help with the day-to-day chores of the garden, some just once or twice, some every week.

Heating the Greenhouses

When Putin’s missiles caused city-wide power cuts last winter, the plant-life inside the garden’s greenhouses was mortally threatened. Roman Ivannikov, the head of tropical and subtropical plants department, works in the greenhouses. During the power cuts, he and other devotees took metal barrels and lit fires within the greenhouses to keep them warm the old-fashioned way. “Very romantic,” he says with a smile. Nonetheless, hundreds of plants perished in the cold. Power cuts are anticipated again this coming winter as the Kremlin continues to strike the Ukrainian capital, thus the campaign to keep the greenhouses heated through the winter and save the living collection within that has been designated a ‘national treasure’ of Ukraine.

Both the garden and its greenhouses are testament to the mutually caring relationship that can exist between nature and humans, and of the local community’s dedication to conserve and nurture under the shadow of Putin’s war. The garden offers spiritual sanctuary, a connection with the past and a means by which to honour the fallen in the heart of wartime Kyiv, as well as benefiting the scientific community and conserving biodiversity.

Ecocide and Inspiration

Ukraine has accused the Kremlin of ‘ecocide’, a crime so far only recognised by a small but growing number of countries (of which the warring parties are two). With the invasion floundering and its army fragmented, the Kremlin has resorted to a strategy of non-conventional warfare which entails deliberate ecological destruction unprecedented since the US use of ‘Agent Orange’ in Vietnam, such as the targeting of chemical factories and the explosion at the Kakhovka Dam.

The story of a community’s dedication to preserve and protect the Hryshko Botanical Garden and its greenhouses is one of many examples of the Ukrainian and human impetus to protect our shared world. As new conflicts spark and extreme weather becomes more common across the globe, the hard work and love of nature demonstrated by Yuri, Olena Roman and others can serve as inspiration for how we choose to face the challenges of tomorrow.

Peli Can Live’s operations are ongoing; read more or donate directly to their projects here, including the Heat for Greenhouses Project, the Semen Oblomei Foundation and the Water for Botanic Garden Project.

Ukrainian Students for Freedom: https://studfreedom.org/en/

Guy Fiennes is a journalist and Rising Leaders Fellow at Aspen UK.