From ‘Haishenwai’ and ‘Boli’ in the Far East and a proposed special economic zone in Siberia to LNG terminals in Murmansk, Russia is fast becoming a Chinese client state.

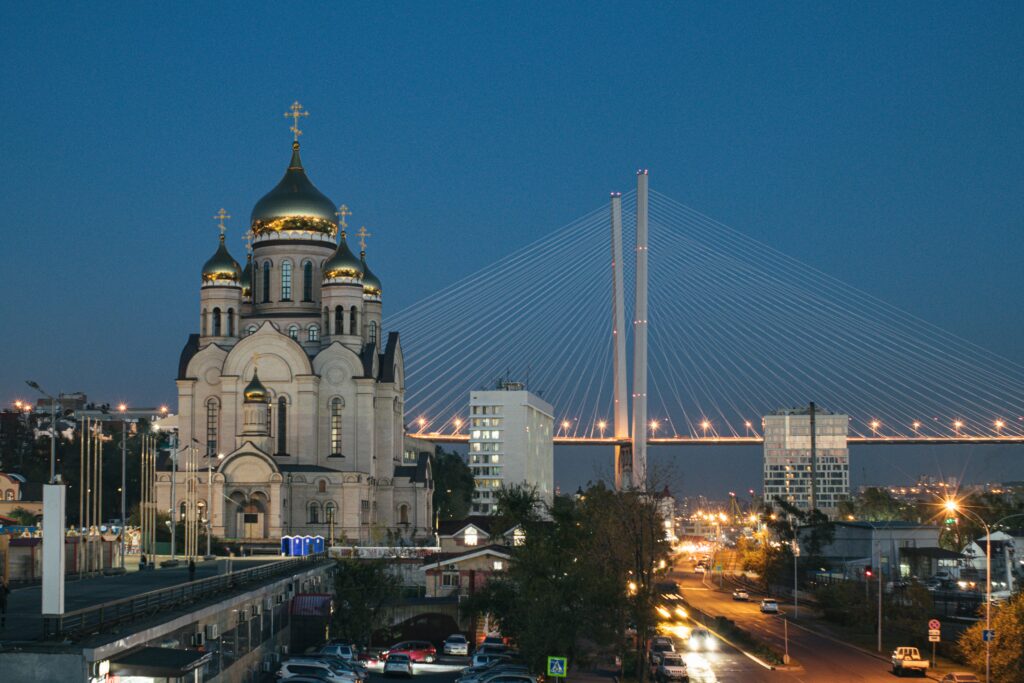

Last month, the Chinese government announced the conclusion of an agreement with Russia, which received relatively little coverage outside of certain Asia-focused outlets: from June 1, the Russian port of Vladivostok would be used as a domestic transit point for the shipment of goods from the North-Eastern border provinces of Jilin and Heilongjiang to customers based in Central and Southern China. This measure is intended to reduce transportation costs for businesses, who so far had to ship their goods via the port of Dalian, which was a lengthy and inconvenient journey that resulted in longer waits and higher prices.

As the Chinese General Customs Administration declared in an official press release, the agreement would be mutually beneficial and ‘win-win’ for both countries. Yet, although the Chinese side has sought to downplay any wider significance that could be attributed to the effective logistical integration of Vladivostok into the Chinese domestic market, this news is symptomatic of a new vassalization of the Russian Federation that was most prominently asserted by French President Emmanuel Macron in a recent interview with L’Opinion in May. It is an assumption that has been publicly challenged both by the Russian and the Chinese side. Thus, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov has countered Macron’s argument claiming that Sino-Russian relations were ‘equitable and mutually respectful’ Meanwhile, the CCP-controlled Global Times has sought to dissipate any impression of a shift of power from the Kremlin to Zongnanhai by arguing that the Vladivostok agreement was part of a long-term Russian development strategy for the Far East that also conveniently matched the Chinese goal of revitalising its Manchurian border provinces. As the Kremlin foreign policy advisor Sergei Karaganov, has bizarrely argued because of the two nations’ alleged ‘cultural-genetic’ differences Moscow would never become subordinate to Beijing’s interests. Yet the facts speak a different language.

Since the beginning of Putin’s failing invasion of Ukraine in February of last year and the introduction of an unprecedented package of sanctions that have severed vital trade links with Europe, Russian dependence on China has only grown in every economic category, but especially in such war-relevant goods as electronics, technical spare parts, and other so-called parallel imports – meaning goods that are officially destined for one country, which acts as a transit state for the ‘real’ end consumers located in a sanctioned state such as Russia. Countries such as Armenia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, have equally seen their trade with Russia reach new heights. Lately, however, the United States and its NATO allies have started clamping on these illicit commercial flows, meaning further difficulties in obtaining both consumer goods and much-needed industrial hardware to keep the war going and the home front functional, await the Russian economy. This makes China an even more important partner for Russia than it already is and further increases Beijing’s leverage over Moscow.

Yet while China has supported Russia diplomatically and economically, it has skilfully avoided tying its fate too closely to that of its northern neighbour and instead has worked towards a situation in which Beijing will be able to call all the shots in the countries’ bilateral relations going forward. A case in point for this development is the Chinese negotiation strategy regarding a new Siberia 2 pipeline that should symbolize Russia’s economic reorientation towards the East but instead reveals Putin’s growing dependence on Xi Jinping’s goodwill. As the Financial Times reported, the Chinese negotiating strategy with Moscow essentially consists of maximising concessions from Russia as the Ukraine war drags on with catastrophic losses in men, resources, materiel and global prestige. Time is on Beijing’s side and depending on the situation at the front, its demands can be adjusted, extended and refined at will. Already, China has scored a major foreign policy win when Putin declared that Russia would start using the yuan ‘in payments between Russia and countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America’.

The Chinese transformation of Vladivostok into a domestic transit port appears as yet another, opportunistic move in a decades-long pearl string strategy which foresees the acquisition of stakes or concessions in strategically important ports around the world that can then act as commercial hubs for Chinese businesses and as bases for the People’s Liberation Army Navy. In pursuit of this goal, last year the Chinese government-controlled shipping company Cosco acquired a stake in the German port of Hamburg – a move that was criticized not only by German opposition parties in the Bundestag but also by members of Olaf Scholz’s government as a reckless abandonment of sovereignty over a critical asset to a revanchist People’s Republic. However, in contrast to other investments in foreign ports and facilities made in the past, China can justify its move into Vladivostok by pointing to historical grievances that go beyond the mere economic rationale and touch a traumatic sore point in the Chinese national psyche: the painful memory of European colonialism throughout the 19th century.

As Chinese nationalist bloggers, journalists and even diplomats have pointed out, the city had once been known as Haishenwai (‘Sea Cucumber Bay’), until Russia acquired it, along with the province of Outer Manchuria in 1860 in one of the so-called Unequal Treaties in which European powers managed to gain large territories from a weakened Imperial China. Beijing has not forgotten the countless degradations and losses of both people and territories it suffered during the so-called ‘century of humiliation’ and periodically keeps reminding the world of its long memory and its intention to right perceived historical injustices. Interestingly, the Chinese Ministry of Natural Resources has recently released a regulation, which orders both provincial and national authorities to use Chinese place names when referring to a string of Russian locations in the Far East. Under the directive, going forward, Vladivostok would officially be called Haishenwai on state-authorized Chinese maps of Russia.

Through such subtle, yet symbolically highly significant measures, China appears to be conditioning its population to perceive Vladivostok and other cities in the Russian Far East as ‘actually’ and historically Chinese territories that were unjustly stolen by European powers during the ‘century of humiliation.’ Apart from Vladivostok, other cities and territories that are marked for renaming according to the Ministry’s new regulation, are the border town of Khabarovsk (‘Boli’) and the gas-rich island of Sakhalin (‘Kuyedao’).

Yet Beijing’s ambitions already go much further than Vladivostok and Siberia and stretch across all of Russia’s eleven time zones. Thus, recently, China seems to have been attempting to gain an initial foothold in Murmansk, close to the Norwegian border, by proposing to finance the construction of LNG terminals in the Arctic city. A local Russian businessman called for two Chinese enterprises involved in the proposed scheme to be exempted from paying dividend taxes, to allow further Chinese investments in LNG terminals in the Russian Arctic region. Yet this is not all. In December of last year, in a highly interesting piece, The Asia Times also drew attention to Sino-Russian plans of creating a special economic zone for Chinese investors in the Russian Far East that would allegedly span 6.69 million square kilometres and open Siberia and its vast resources up to businesses from the People’s Republic. A likely future target for Chinese strategists could also be the resource-rich, but sparsely populated Peninsula of Kamchatka and specifically the island’s administrative centre, the port city of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatksiy. Gaining a commercial or indeed military foothold or base in Kamchatka would allow China to exert its influence both in the Pacific and into the Arctic, two of the most strategically important regions of international competition in the coming decades.

Putin’s obsessive dream of re-establishing a Russian/Soviet sphere of influence in Europe and the disastrous decision to invade Ukraine, have left him with little choice but to turn to his ‘old friend’ Xi. China now has the unique chance to turn Russia into its client state. The process of vassalization has already begun. It is unclear where and when it will end.