The time Stalin pulled off a heist makes for an unexpectedly entertaining novella plot.

There are few more towering figures in 20th-century history than Joseph Stalin. The Soviet dictator ruled his country with an iron fist, and while estimates of the deaths he caused vary widely, a credible figure is 20 million. A true monster, he would only have continued had he not died. Prior to his passing, he was readying a show trial of nine doctors, seven of them Jewish, and some believe it would have been the prelude to a wider campaign of violence, perhaps even genocide, against Russia’s Jewish population.

So, how did this man come to seize the Soviet throne? How was he able to supplant all his rivals, not least Leon Trotsky, to become unassailable for over thirty years? As with the Second World War, or the rise of the Nazis and Hitler, readers might presume there is nothing left to be written about these events. But as with many authors writing on these subjects, David Tallerman has discovered untapped territory. His historical novella focuses on one small but key event in the history of Stalin’s rise: the time he masterminded a bank heist.

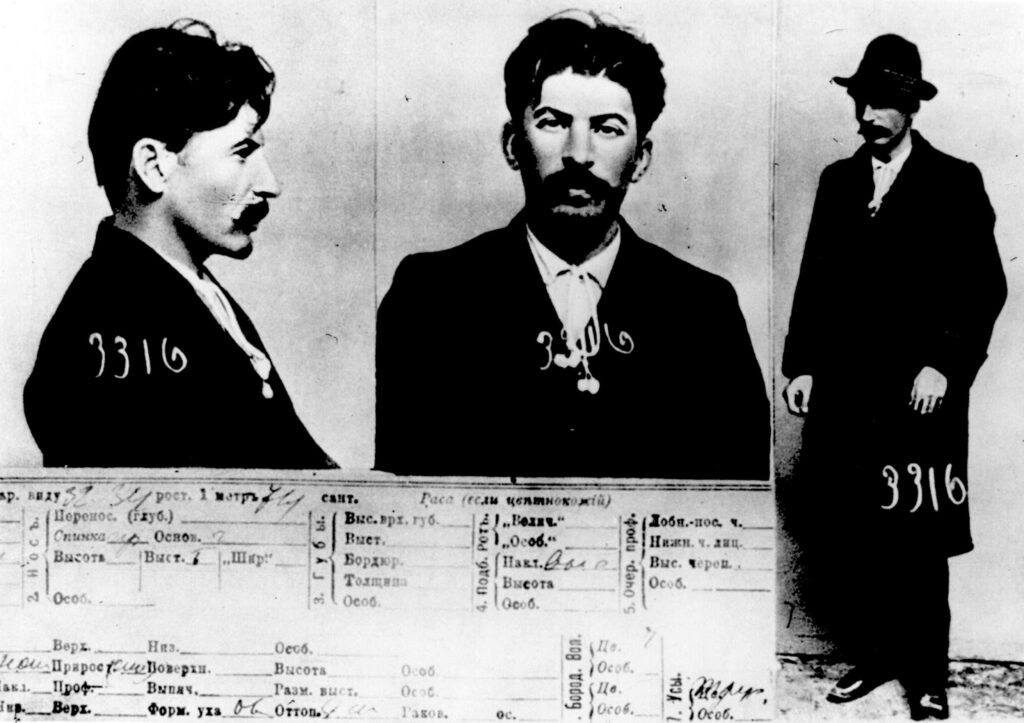

In 1907, Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvil, was yet to be Stalin. His parents’ only child to survive infancy, they nicknamed him Soso (a diminutive of Ioseb). Later, after enrolling in a seminary to train to become a priest, he joined a forbidden book club and adopted the nom de guerre Koba, from the bandit protagonist of Alexander Kazbegi’s novel, The Patricide. After abandoning the priesthood, he lived up to his namesake and was linked to The Outfit, a band of revolutionary outlaws who robbed and pillaged throughout the city of Tiflis (now Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, but back then part of the Imperial Russian Empire).

David Tallerman’s novella opens with Koba meeting with Lenin in Tammerfors, a city in southern Finland. They are attending a Bolshevik conference and the Georgian bandit is rough and coarse in comparison with the intellectual revolutionary leadership. But Lenin takes him aside and encourages him to not just keep on committing robberies for the cause, but to escalate what they refer to as expropriations. Koba returns to Tiflis under no illusion that fulfilling Lenin’s wish will be his ticket into the upper echelons of the movement.

In Tiflis, Koba meets up with The Outfit, amongst whose number is Simon Arshaki Ter-Petrosian, who goes by the nom de guerre, Kamo. The leader of The Outfit is Kote Tsintsadze, but he is reticent about Koba’s plans to seek bigger targets. It isn’t long before he’s arrested by the Okhrana, the Czar’s hated secret police. Kamo takes charge; he is someone with far fewer scruples, a lust for excitement, and a very high threshold for physical pain. Koba, meanwhile, befriends a bank clerk and learns of a large transport of money. Kamo and The Outfit now plan the heist.

David Tallerman has written a novella which truly brings history alive. In an Afterword, he writes that unlike many writers working on stories based on historical events; he wasn’t faced with too little source material, and hence the need to take fictional flights of fancy, but too much. Indeed, he lists just two scenes in which he exercised creative licence. One of these, a confrontation between a fictional police officer (the only made-up character in the narrative), and Kamo and one of his acolytes at a train station in the heist’s aftermath, is grounded heavily in real events. The other, how the money was moved from Kamo’s hideout to where it was secreted, he needed to fictionalise who transported it and how. But apart from this, the rest of the narrative is based on historical sources.

While the events depicted are undoubtedly gripping, the novella’s strongest feature is its cast of characters. The well-known cliché fact is stranger than fiction is truly apt here. Kamo has been lost to history and Tellerman deserves praise for bringing him back. Indeed, in the afterword, he rightly says that he’s deserving of his own book. A violent but highly intelligent criminal, he took delight in adopting disguises and befuddling the Czar’s forces. In later life, during the civil war which broke out immediately after the revolution of 1917, he became a brutal Red Army commander. He’d test new recruits by faking their capture and having them dragged into the forest. Those who were stoical in the face of execution, he let live. Those who showed fear, he executed for real. Then there was the occasion he cut open a man’s chest to pull his heart from its cavity.

But while Kamo steals the limelight, this story is really about Kober, because the reader knows he will become the monster who caused the Soviet Union, and indeed the world, so much pain and terror. Yet he’s absent from much of the narrative, and belies expectation by, mostly, keeping his hands clean. How does he manage this? The author has him as an informant for the Okhrana and certainly, there is much in the historical record to suggest he was. But if so, as portrayed in this novella, he played them at their own game and very much made them serve his purposes. Because what comes out of The Outfit very well is how cunning the future Stalin was.

At the outset of Tellerman’s story, at the conference in Tammerfors, the intellectuals of the Bolshevik high command regard Koba with embarrassment, if not contempt. Of course, as readers, we know many of them will die at his hands, having been forced to “confess” their crimes in show trials. But all that’s for the future and as the narrative unfolds, readers are introduced to a gruff and unpolished bandit, yes. But one who outwitted his contemporaries, such as Kamo, his enemies in the Okhrana, and his superiors in the Bolshevik leadership. Always one step ahead, Koba orchestrated events masterfully, pulled off a successful heist, and bought his way to a prominence which would eventually allow him to secure his horrifying destiny.

David Tallerman, The Outfit: The Absolutely True Story of the Time Joseph Stalin Robbed a Bank (Rebellion Publishing), pp. 208, 8,99£.

A journalist and author, James worked for over 10 years in Current Affairs television and documentaries, researching and producing films for Channel 4 Dispatches, PBS Television and National Geographic.