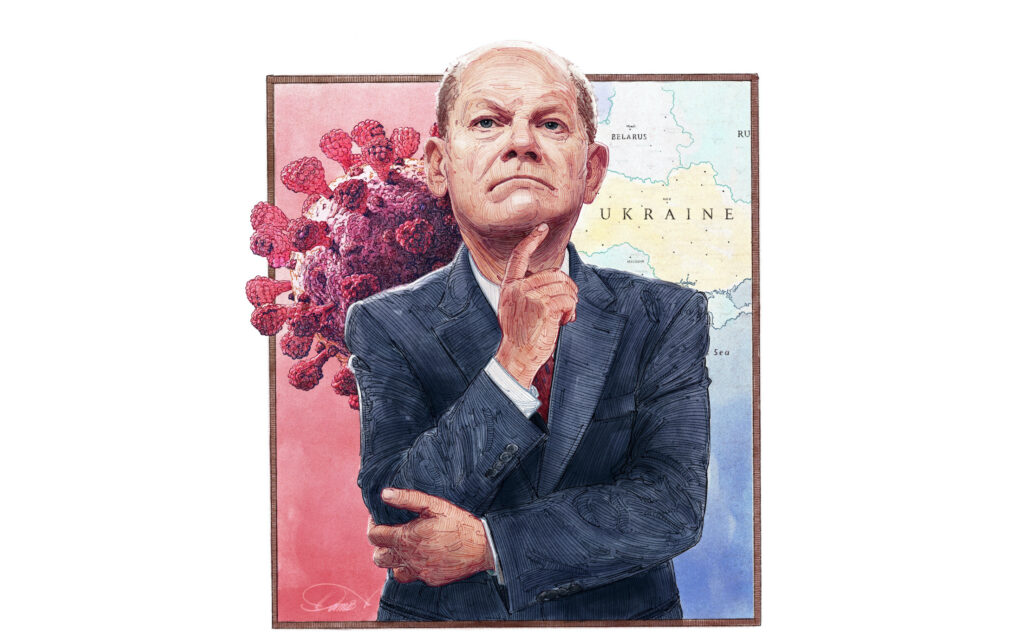

Olaf Scholz has a plan. But he won’t say what it is. A TNV profile of Germany’s new Chancellor.

The Chancellor, like so many Berliners in a city of continuously rising rents and property prices, is a commuter. While Merkel famously occupied an apartment opposite of Berlin’s Pergamon Museum for Antiquities, overlooking the Spree River, Olaf Scholz privately resides in nearby Potsdam, the picturesque capital of the state (or Land) of Brandenburg which can be reached within forty-five minutes from his modernist offices on the seventh floor of the Chancellery that faces the Bundestag, Germany’s national parliament. Since the days of the so-called Chancellor-Bungalow in leafy Bonn on the Rhine, no German head of government has lived in state property and while the Chancellery provides a small studio-apartment to the head of government, the building is not comparable to the White House, No10 or The Elysée Palace in Paris. Instead, home, for Scholz, is out near the wild-romantic lakes surrounding Berlin, in a constituency he has been representing since his election victory last year as an MP in the Bundestag. He won his seat directly with a solid 34 percent of the vote, beating his Foreign Minister and fellow Potsdamer Annalena Baerbock who got 19 percent. Born and raised in the West-German province and made – politically, emotionally, culturally- in cosmopolitan Hamburg, Scholz now proudly calls himself a ‘Brandenburger’ a moniker that only a decade ago would have carried the social stigma of Ossi, ‘East German’. Yet, more than thirty years after the nation’s reunification, the Chancellor genuinely identifies with the state and its people, whom he considers as sober, modest and stoic as himself. As a native West German elected for an East German seat, Scholz is the first Chancellor to symbolise the country’s rewon unity in his own person.

Like no other place in Germany, Potsdam has been the architectural playground of Prussia’s monarchs and especially Frederick The Great, the ‘philosopher-king’ who erected his phantastically opulent Rococo residence Sanssouci (‘Without Care’) in the city and is buried next to his two favourite dogs in the palace’s park. Destroyed during the Second World War and rebuilt by the Stalinist East German regime, Potsdam today has a strikingly eclectic look that sees Soviet-style apartment blocks reminiscent of suburban Moscow kissing the backyards of classicist Lutheran churches.

After the country’s reunification in 1990, Postdam quickly became a favourite domicile for wealthy Berliners and national celebrities seeking to flee the daily hubbub of the capital without yet fully losing touch with it. One of Germany’s most popular show-masters, Günther Jauch relocated to Potsdam and has since invested considerable sums in the reconstruction and restoration of some of its historic landmarks, while the fashion designer Wolfgang Joop, a born and raised Potsdamer, has his company headquarters in the classicist ‘Villa Wunderkind’ on the banks of the Heiliger See, the Holy Lake. While, at least to international audiences, Olaf Scholz might soon become the most prominent Potsdamer, he does not seem to care much about, nor appears to be particularly affected by the ceremonial pomp and publicity that naturally comes with the office of Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany. On the contrary: on formal occasions, such as during state visits and receptions for foreign leaders and dignitaries at the Chancellery, he looks almost embarrassed by public attention and the military honours presented to him by the Bundeswehr’s elite Guard Battalion and he has yet to find a signature hand-gesture as iconic as Merkel’s rhombus of power.

Although there are pictures of Scholz attending red-carpet events in Hamburg in his capacity as First Mayor, on these occasions he always looked somewhat oafish and distinctly out of place next to film stars such as Ewan McGregor, Gregory Porter or the German actor Kida Kodr Ramadan (5 Blocks). Instead, he seems most at ease in the company of civil servants, seasoned technocrats and long-standing confidants, such as his Minister of the Chancellery (in effect the federal government’s chief-of-staff), Wolfgang Schmidt who joined Scholz as a personal assistant in 2002 when the latter was General Secretary of the SPD and who is now in charge of supervising the nation’s various intelligence agencies. Schmidt has been described as Scholz’s gregarious factotum, the most loyal and trusted person in the Chancellor’s professional orbit. As Germany’s lord of secrets, he is one of the most powerful, unelected political operators in Berlin and by extension, Europe. At the same time, he is also very active on Twitter, where he is commenting on everything from football (he supports Hamburg’s left-wing club 1. FC St. Pauli) to Ukraine and Germany’s G7-presidency.

In Potsdam, Scholz occupies an apartment in the lovingly reconstructed historic city centre, opposite of the state parliament, where his wife Mrs. Britta Ernst, as he calls her publicly, is serving as the current Minister for Education in the SPD-led red-green-conservative coalition that has been governing Brandenburg since 2019. Ernst is considered an experienced lawmaker in her own right and she enjoys a high national reputation as an expert in the field of education policy. Like Merkel’s husband, the Berlin professor of physics Joachim Sauer, Mrs. Ernst is unlikely to prioritise her husband’s political and representative duties over her own. And neither, as Scholz has stressed in interviews, would he want her to. By all accounts, theirs is a childless, loving and respectful marriage of complete, self-made equals; of SPD sweethearts who met in the party’s notoriously rebellious Socialist youth wing and reached the pinnacles of German national and state politics. They can, unironically, be called a quintessential power couple; unparalleled in recent German history and a novel phenomenon in the nation’s political landscape, yet reliably free of even the slightest whiff of glamour, controversy or scandals.

Like Merkel before him, in his public demeanour, Scholz comes across as an unassuming, unpretentious figure who, as his fellow Social Democrat and personal friend Andrea Nahles once remarked, draws most satisfaction from the efficient execution of meticulously laid plans. His speeches are monotonous in tone, excruciatingly technical in content and often torturously long-winding. In contrast to the East German Merkel who could talk to Putin in Russian, Scholz speaks fluent English with a crisp, North German-Hanseatic tang to it. Inevitably, in his understated and cool, almost detached manners and dour suits – which as the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung has speculated, were once bought off-the-rack, but now appear tailored to his measurements -, Scholz always sounds and looks like any other mid-level civil servant in a Berlin Ministry; undoubtedly competent and on top of all the relevant material, data and debates in his specific field of expertise, but not necessarily charismatic and by no means an exciting public speaker. A German columnist once fittingly likened Scholz’s personality to that of a diligent departmental head who takes you aside at a late-night office party to remind you to clean up an excel sheet before sending it to the client in the morning. He is reportedly a tough negotiator, who always seeks to be better prepared than his counterparts and is known as a detail-obsessed Aktenfresser, a ‘file-eater’. True to this image, he still carries a worn, forty-year-old, bulky and utterly unfashionable leather bag as a sort of personal totem wherever he goes and his self-confessed guilty pleasure is Käsebrot, a black bread sandwich with cheese, the clichéd Tupperware lunchtime-treat of the German office worker. Yet, while in other countries such an aura of bureaucratic dullness might present a significant impediment to a successful political career, in Germany Scholz can almost be considered a man of the people.

In hindsight, Olaf Scholz’s rise to the top was as unpredictable and outlandish to most observers, as it now appears strangely obvious and almost inevitable. Yet, only six months ago, only few journalists would have wagered much on Olaf Scholz’s candidacy for the office of German Chancellor. One year earlier, the then Finance Minister and Vice Chancellor had been chosen by Germany’s Social Democratic Party to enter the race to succeed Merkel. He was an odd choice; a technocratic centrist in a party that was drifting ever left-wards and which was haunted by a political trauma that had haunted the party for almost two decades.

Since Gerhard Schröder’s loss to Merkel in 2005, a series of Social Democratic chairmen had unsuccessfully attempted to take on the venerated ‘Mutti’ (Mother) of the nation, only to be relegated to junior-partner positions in Great Coalitions headed by the Christian Democrats. In the meantime, the SPD descended into factionalism and heated arguments over the party’s course in which moderate centrists (organised in the so-called Seeheim Circle) faced off against a powerful cohort of democratic Socialists, who were led by the charismatic chairman of the youth wing, Kevin Kühnert. In this ideological tug-of-war, Scholz who in his teenage years had been a committed Marxist and one-time vice president of the International Socialist Youth was now considered insufficiently left-wing by many members who rejected and indeed humiliated him in his bid for chairman of the party in October 2019. At this point, under normal circumstances, Scholz’s political career would have likely ended as a respected backbencher in the Bundestag, followed by a return to practising law in Hamburg, the city where he began his political career in the ranks of the SPD’s rebellious youth wing and which he governed as First Mayor from 2011 to 2018. Realistically, only a world-historical shifting of priorities that would have put him squarely in the centre of developments would have given Scholz another chance to reverse his political fortunes. Then came COVID-19.

The pandemic has made, broken and restarted the careers of political leaders around the world. Scholz fell into the last category. A man who reportedly excels in situations of crisis, he used his powerful position as Minister of Finance, to increase his visibility and stature among German voters, taking out the ‘bazooka’, as he called it publicly, by promising to unlock ‘unlimited funds’ to sustain struggling German companies during the pandemic. Still, for almost a year, his poll numbers remained static, hovering persistently around fifteen percent. Yet, while pundits kept focusing on the SPD’s historic weakness, Scholz remained defiantly confident, declaring in January 2021 that he would indeed be Germany’s next Chancellor. A claim which, at the time, seemed to border on self-delusion, but now appears as a statement of almost prophetic patience as during the summer of last year, something remarkable happened: while the CDU’s overly jovial candidate Armin Laschet stumbled over a series of embarrassing gaffes, Scholz, who had served as Merkel’s Vice-Chancellor and Federal Minister of Finance since 2018, moulded himself after the reassuring, larger-than-life figure of ‘Mutti’, going so far as to ironically adopt her signature rhombus hand-gesture for a magazine cover and talking of cabinet decisions ‘the Chancellor and I’ had taken together. As the mastermind behind the SPD’s campaign, the PR Raphael Brinkert and the party’s then-general secretary and current chairman Lars Klingbeil admitted quite openly, this was part of a carefully planned strategy to win the ‘Merkel-voters’, meaning those centrist and moderately progressive sections of the population that liked Merkel’s presidential style but were not ideologically aligned with the CDU. In the end, the great bet succeeded by a hair’s breadth, leaving the CDU in tatters, but Merkel’s political legacy strangely secure in the hands of her Vice-Chancellor. After lengthy negotiations in which seemingly contradictory ideological projects had to be balanced out – a discipline Scholz reportedly excels at -, he formed a so-called traffic-light coalition consisting of his SPD, the Greens and the liberal Free Democrats. The new-formed administration has committed itself to an ambitious program of transitioning the nation’s industry to eighty percent renewable energy by 2030 building 400,000 new apartments every year, and raising the minimum wage to 12 Euros an hour – all while balancing the federal budget in a way that will not violate the Republic’s commitment to a zero-debt policy.

In hindsight, Scholz’s rise to power was as unpredictable to most observers, as it now appears strangely obvious and almost inevitable. However, while Germans have come to know their new Chancellor over the past two years, especially in Britain he is still an enigma to most people. His name might be vaguely familiar from the news, social media and the papers, but he remains a far less prominent figure than Merkel was. Who is Olaf Scholz? What does he want? And how will he lead Germany in the coming years?

More than Merkel, who was guided by moderately liberal Realpolitik tackling whatever crisis or file happened to land on her desk on any given day, Scholz’s politics revolve around more fundamental, classically progressive themes, such as ‘respect’. It is a powerful buzzword that became a central, emotive slogan of the SPD’s victorious campaign and which especially resonated with working-class voters who had previously abandoned the party in droves after Schröder neoliberal turn during the early 2000s, switching their allegiance to left- and right-wing populists. Respect is a theme about which Scholz has spoken with uncharacteristic passion on the campaign trail. To him, it is a central part of a person’s human dignity and feeling of self-worth; yet it also encapsulates the idea of a society that shuns snobbery and treats a builder the same way it would a manager. Crucially, in the Chancellor’s vision of a better, more equitable and compassionate Germany, this emotional appeal to transcend class differences and foster mutual respect between people of different backgrounds is necessarily flanked by economic measures designed to foster greater social mobility and improvements to the nation’s public welfare system. It is important to note that these ideas were not developed in the ivory tower of a political science faculty, but are grounded in a combination of extensive governmental experience and an obsessive, wonky studiousness that is characteristic of the Chancellor and which may sometimes come across as an overpowering, intellectual arrogance.

The reality is that Scholz is no dogmatic ideologue, but a learned and highly educated practitioner of power, who knows exactly how to use the levers of the federal state and Germany’s considerable economic resources for the realisation of his political goals. A lawyer by training, he is an avid reader of history, philosophy and sociology and his only book so far, Hoffnungsland (‘Land of Hopes’), published in 2018, is a testament to Scholz’s wide academic interests, technocratic understanding of politics and analytical personality.

Drifting between lengthy, analyses of challenges surrounding migration and the labour market, citations of Kant, Karl Popper and other philosophers and the presentation of mostly technical and legislative solutions, without ever becoming overly personal, Hoffnungsland is pure, undistilled Scholz. However, it also holds some surprises for the reader. At least in 2018, on Germany’s arguably most divisive issue of the recent past, migration, Scholz held unexpectedly conservative views, as he acknowledged the impossibility to accommodate an annual inflow of millions of refugees to Germany, while he argued for a Canada-style point-system and proposed improvements to the EU’s border management agency Frontex, so to better monitor, register and classify new arrivals. At the same time, however, Scholz also stressed the need to integrate asylum seekers into German society through jobs, education and language training, as well as apprenticeship-schemes and declared himself proud of the warm welcome migrants had received during the refugee crisis in 2015. This multi-pronged, almost dialectic approach to migration is classic Scholz and characteristic of the Chancellor’s style of politics. It is telling that during the height of last year’s refugee crisis, he supported Polish efforts to build a border wall with Belarus in order to sabotage Lukashenko’s strategy of destabilisation, while also offering support to asylum seekers who wished to return to their countries of origin.

Reviewing his public speeches, past legislative achievements and Hoffnungsland, it becomes apparent that to Olaf Scholz, government means, first and foremost, the optimisation of administrative pathways through which ‘reasonable’ (vernünftig) or ‘smart’ (klug, one of the Chancellor’s favourite words) policies can be executed. International relations, on the other hand, are conducted as the old, Bismarckian art of the possible which requires the balancing of different interests and competing political, economic and social priorities. Scholz’s masterpiece in this regard and the one achievement he has been proudest of in his capacity as Federal Minister of Finance was the introduction of a global minimum corporate tax standard accord which was signed by 136 countries. It was a triumph of German fiscal diplomacy which was hailed by the conservative commentator Robin Alexander as a resounding success for Berlin’s particular form of social capitalism. It is also a victorious conclusion of decades-long Social Democratic efforts to level the economic playing field and combat tax evasion by multinational companies.

While the global minimum corporate tax accord is Scholz’s most significant international accomplishment so far, during the election campaign, his pitch to voters was notably more domestic than that of any of his competitors, focusing on an expansion of public housing, a moderate minimum wage increase and stable pensions. Yet, the office he has assumed and his predecessor’s European projection of Germany’s economic power, has necessarily forced him into the role of an important diplomatic partner and crisis manager, both in the EU’s pandemic response, as well as the Ukrainian crisis. It is a position that requires him to divert time and attention away from fulfilling his electoral promises of social reform. But as Merkel’s legacy continues to shape the early stages of his chancellorship, Scholz, as an SPD election poster proclaimed, just ‘gets on with the job’.

In the Ukrainian crisis, the Chancellor has to balance multiple, conflicting priorities and interests within his own party, three-way coalition-government, the German public, the EU and the NATO alliance. Domestically, the Chancellor is bound by his government’s commitment almost completely to transition the country’s economy to clean, renewable energies within the next ten years; an extraordinarily ambitious and superbly complex goal that will make it, at least temporarily, necessary to rely on natural gas imports from Russia through the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. Western sanctions against Moscow would also result in permanently higher energy prices which, coupled with rising eurozone inflation, would pose a financial burden for lower-income families who have just found their way back to the SPD and whose support Scholz will need to stay in power.

Among Scholz’s own Social Democrats, opinions on Russia are split between those who favour and, like ex-Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, actively lobby for a continuation of Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik, meaning transactional rapprochement with Moscow, and those who want Germany to join the United States and Britain in a tougher stance towards Putin. His coalition partner, the Greens, have at least partly shown themselves critical of the pipeline project, while the government remains publicly committed to a long-standing, yet not always enforced principle of not exporting weapons into crisis regions. On the other hand, Scholz also feels himself bound to Germany’s NATO-obligations and the protection of the EU’s Eastern European member states that live in perpetual fear of Russian aggression. It is this complex of conflicting interests that have bedevilled the Chancellor’s first two months in office and which have resulted in a false appearance of German indecisiveness, weakness and even indirect collusion with Moscow. In fact, behind the scenes, the Chancellor has been busy building a European alliance that can act as a conduit between the United States, Ukraine and Russia. It is significant that on the same day that Macron visited Putin in the Kremlin, Scholz was at the White House, conferring with Biden. These dialogues were followed by talks between France, Germany and Poland in Berlin, in a strategic format called the ‘Weimar Triangle’, as well as unfruitful attempts to revive the so-called Normandy format with Ukrainian and Russian representatives. The peculiar silence or public ‘invisibility’ of Scholz during the crisis is not due to any lack of leadership qualities, as the CDU’s newly-minted chairman Friedrich Merz has claimed in the Bundestag, but a direct consequence of his understanding of politics. He believes that those in government should avoid unnecessary rhetoric, and instead concentrate on achieving tangible political results. Scholz knows that the Ukrainian crisis can only be solved through high-level dialogues with Moscow which, as Macron has noted, will require taking Russian security interests into account. Sabre-rattling, media hysteria and premature announcements of specific, punitive measures on the other hand – as practiced by the Americans and the British – are simply not the way Scholz conducts political negotiations. Instead, the Chancellery’s current diplomacy aims to revive the Minsk II Agreement which has been described by Macron as the only way to achieve a peaceful resolution of the crisis. A master of the fine print, it can be assumed that Scholz will aim to achieve compromises in partial areas which will allow Russia a face-saving retreat, while securing the completion of Nord Stream 2. It is uncertain if this strategy will prevent a war in Ukraine. What is certain that in the Chancellor, Putin will encounter a well-prepared, skilled negotiator and a man whose focused professionalism will be an asset in defusing the current tensions and re-engaging Russia on issues of European security in a peaceful, constructive manner. In the meantime, Scholz is keeping the Kremlin and everyone else guessing what his next move will be – which is just the way he likes it.

On the Covid-front, his second great challenge, the Chancellor has been steadfast and passionate in his appeals to the public to get vaccinated and boostered, while he has also shifted his position on mandatory vaccinations from opposing them publicly on the campaign trail, to embracing them while in office. This public inconsistency is highly untypical for Scholz and appears to have cost him some credibility among centrist voters who, as polling suggests, in recent weeks have shifted back to the Christian Democrats. While Scholz knows that he has the majority of the German public on his side, within his own government, he faces opposition. While the Greens support general mandatory vaccinations, large parts of the liberal FDP reject such measures as incompatible with personal freedom and civic self-responsibility. The Chancellor appears to have found a characteristically pragmatic middle way, by making the issue of mandatory vaccinations a vote of conscience (with himself intending to vote in favour of it) and leaving legislative initiatives to individual groups of lawmakers in the Bundestag. However, as it is highly unlikely that any consensus will be reached in Germany’s national parliament, the handling of the crisis will most likely revert to the Chancellery and the SPD-led Health Ministry which will continue its drive to boost vaccinations and slow down the spread of the Omicron-variant. It is safe to assume that Scholz, in characteristic fashion, will study the files, continue leading his administration’s response to the pandemic and simply ‘get on with the job’.

As he nears the symbolic threshold of his first hundred days in office, the new Chancellor finds himself in a difficult position. While his government recently fulfilled an important SPD-election promise when it announced an increase in the hourly minimum wage to 12 Euros, the public’s attention has been diverted by the pandemic and the increasingly threatening situation along the Ukrainian border. Does this bother Scholz? It is possible, but unlikely. Political success, to the Chancellor, is measured in results, rather than speeches. He knows that if he manages to deliver on his bold domestic agenda, the German electorate will likely return him to the Chancellery in 2025. On the other hand, he will continue to find it difficult to extract himself from global challenges, including the Climate Crisis that have the potential to influence public opinion in greater ways than any successes achieved in the expansion of public housing and the possibly elusive fostering of ‘respect’ among Germans. Balancing international commitments and domestic priorities will thus be the Chancellor’s preeminent task that will decide if his government has a future beyond the next election and whether, as the SPD’s new leadership has declared, the next decade of German politics will be shaped by the Social Democrats.