The recent protests in Kazakhstan have brought the country back into the focus of Western media audiences. But for a decade now, China and America have been competing for political influence, resources and markets in one of the world’s most important regions.

The shadowy ‘Great Game’ for Central Asia between 19th century Britain and the Russian empire was in fact largely a fiction, a literary fantasy, a political construction to project images of power especially to domestic audiences. With different players, in a more global scenario, the fiction has continued into the 20th and 21st century. During the Cold war, the USA engaged the Soviet Union mostly in Europe and East Asia, to some degree in Latin America and very little in Central Asia, even if we stretch it to include Afghanistan and Iran. After 1989, the much-debated and tragical invasion of Afghanistan has ended with a hasty US withdrawal, while China has regionally flanked the USSR/Russia, in economic, as well as security terms.

Faced with new geopolitical constellations and intensifying Sino-American rivalries, it is reasonable to ask if a new ‘Great Game’ is underway. Once again, so far fictional elements have prevailed. After all, why indeed would the world’s ‘great powers’ engage in Central Asia? In fact the overall regional population is slightly more than 70 million; furthermore, according to recent figures from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), as of 2020 just some 2% of the world’s oil reserves and 7% of natural gas reserves would be located in Central Asia. What is then all the talk on Central Asia and great games about?

Until 1992, most of Central Asia used to be a part of the Soviet Union which had inherited it as part of the large bankruptcy mass that was the Russian empire after the First World War. This was true for Kazakhstan, which is almost as vast as India but has a scanty population of less than twenty million, Uzbekistan (with roughly 35 million and a legacy dating to the trading cities of Bukhara and Samarqand, among others), and smaller Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. Afghanistan remained independent and fought back the Soviet invasion of 1979. The whole region was traditionally a crossroads of peoples, both nomadic (such as the Turkic and Mongolian tribes, the armies of Genghis Khan and Timur) and sedentary (from the Persians to Alexander’s Greeks), and the site of routes of trade and exchange, material and cultural, with the historical development of the Silk Roads since ancient Roman and Han times. In a sense, Central Asia’s economic importance declined after the European invasion of the Americas, followed by that of Africa and Asia, and the preference for faster sea trade. Is the world’ geoeconomics changing? Perhaps it is not – about 90% of goods is still traded by sea. And yet China, Russia, the USA and other external players are all somehow involved in the region, and the symbolic echoes of the ‘Great Game’ and the ‘Silk Road’ remain strong, to the detriment of the local populations, who are no victims whatsoever and have enough energy, vitality, and material assets to conduct their lives as they wish, far away from often predatory outsiders.

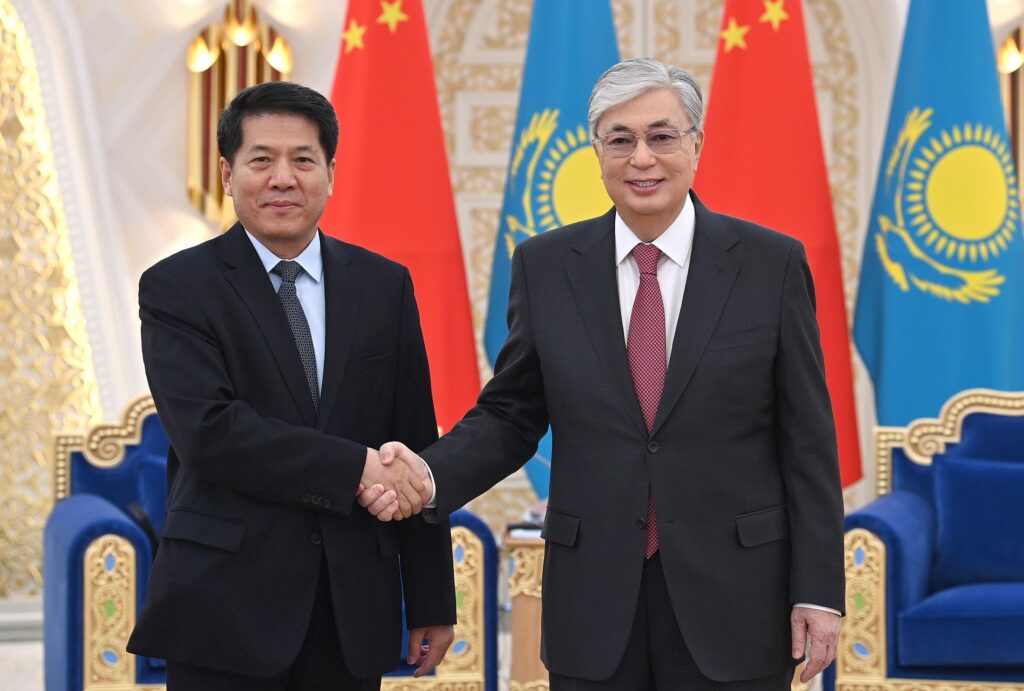

‘Silk Road’ is such an attractive term that China’s President Xi Jinping set out to bring it back into life. In September 2013, in Astana (now: Nur-Sultan), the glitzy new capital city of Kazakhstan, he mentioned for the first time the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), which, together with the Maritime Silk Road (MSR), would give birth to a new, giant ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI), a project of trade, investments, and exchange encompassing Eurasia, Africa, and potentially beyond. In fact the BRI/SREB is already following a wave of massive Chinese investment in the region and officially kicked off in Astana also as a sign of recognition of Central Asia’s role in it. Central Asia would be a springboard for investments, especially in energy, transport and infrastructure, a connective belt with Europe and Russia, and a neighbour of China’s restive Xinjiang/Uyghuristan province, itself inhabited by people of Central Asian origins, including at least Uyghurs, Kazakhs and Kyrgyz. In few years, economic relations between China and the region took off. In reality, China had early secured what it wanted most, especially from Kazakhstan. In 1997 China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) had taken over 60% of AktobeMunaiGas, a large Kazakhstani hydrocarbons producer; in 2005 it had bought PetroKazakhstan, another oil and gas major. Meanwhile, Kazakhstan and China were building the first oil and gas pipelines connecting Central Asia to a country other than Russia, that is, China. In other words, the BRI was already a fact. And China, not Russia or the USA, had become Kazakhstan’s main partner in trade and investments. Somehow similar patterns occurred in the other Central Asian countries. China is also the leading trading partner of Uzbekistan, where it has invested in industry, too, including in car making. As of 2019, Beijing was also the largest exporter to poorer Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, enjoying an overwhelming domination of their markets, especially in the industrial sector. Turkmenistan, a top gas producer, was in 2018 selling to China almost 95% of its gas. This is quite telling about a country which until the Cold war’s end was basically an energy appendage of Russia.

In summary, China has economically taken by storm a region which was traditionally tied to Russia. But what has been the USA’s approach to Central Asia? And how has America reacted to the BRI’s developments in the region?

In the early 1990s, Central Asia seemed to open up a wealth of opportunities to Western investors, especially from the USA and in the Kazakhstani energy industry. In 1993, Chevron and ExxonMobil, with a joint share of 75%, formed a joint venture with KazMunaiGas and LukArco to give shape to a new company, Tengizchevroil, and develop massive oilfields along the Caspian Sea. More investments by US majors followed in the 1990s and early 2000s with the discovery of other Caspian gas and oil fields, and that of the giant Kashagan field in 2000, always with the involvement of ExxonMobil. A new bonanza seemed to be at hands. At the same time, the ‘shock therapy’ proposed to the former USSR by Western (especially US) politicians and companies started backfiring. Between 1991 and 1995, Kazakhstan lost 40% of its GDP. Privatisations and deregulation brought about unemployment, poverty, social disgregation, and a high degree of corruption. While President Nazarbayev strengthened his authoritarian powers and shifted to a more pro-Russian foreign policy, one of his US advisors, James Giffen, was accused of bribery in relation to the concessions of the Tengiz oilfields. Kazakhstan capitalism – boosted by its more powerful American counterpart – looked like a wild market economy tainted by scandals. Yet in the 1990s cooperation between Kazakhstan and the USA flourished in the field of nuclear non-proliferation, with the former dismantling its atomic arsenal with American assistance. The US also enjoyed cordial relations with Kyrgyzstan, which it helped with humanitarian support in exchange for economic and democratic reforms. Not much was achieved in Tajikistan, a victim of a tremendous civil war in 1992-97. Relations between the USA and the two reclusive dictatorships of Niyazov in Turkmenistan and Karimov in Uzbekistan remained less developed.

9/11 and the subsequent war in Afghanistan inaugurated a phase of more cordial cooperation. All Central Asian countries, wary of international terrorism, supported US initiatives in the region and Kyrgyzstan even became host of a military base in Manas. Even Uzbekistan supported US war efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq. Yet the American endorsement of the so-called ‘coloured revolutions’ in the following years contributed to a cooling of relations. After the repression of the Andijan protests in 2005 and the ensuing US criticism, Uzbekistan turned its back to DC, strengthened its ties with Moscow and Beijing, closed US military activities in the country, kicked off Western media and NGOs and suspended the already timid ongoing reforms. Turkmenistan never delivered on promises of political change, nor did Tajikistan. Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan maintained better transatlantic links, although mostly on economic issues. The whole region moved closer to Russia on security matters and welcomed Chinese investments. Relations between the USA and regional governments remained stagnant for some time, apart from some engagement on economic issues. Authoritarianism strengthened, human rights abuses continued, and the Obama administration, which was already tackling the global economic crisis, the ‘Arab Spring’ and its aftermath, the Ukraine crisis, and China’s momentous rise, had difficult time dealing with Central Asia.

In 2012, however, the USA launched a strategic partnership with Kazakhstan and intensified its dialogue with Astana. Even more important, in 2015 Washington inaugurated the 5+1 platform of dialogue with all five ex-Soviet Central Asian countries. In the first place, it is a response to the BRI and Russia’s concomitant Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which includes Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. At the same time, it is a recognition of the importance of a region which is strategically located between Russia, China, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, and Europe and is a source and a transit of terrorist, criminal and other illegal activities. Yet, despite Obama and Secretary of State Kerry’s good intentions, not much has been achieved. Instead of being used by oil majors, Central Asia (especially some countries and regions, such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan) requires sustained investments and strong financial support – Tajikistan for instance is by far the poorest country in Asia (apart from war-beleaguered Afghanistan). While the 5+1 framework has introduced collaboration on significant issues such as NATO’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, climate change and the pandemic, at the same time economic cooperation has so far not been strong enough. What can the USA do to compete with the BRI? Too little, too late?

Two interesting developments are, however, worth mentioning.

First, the new President of Uzbekistan, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, elected in December 2016, has started a significant process of political and economic reforms, taken on the mantle of regional diplomatic leadership, and reopened to the West and the USA. Amongst other things, Mirziyoyev has dismantled the Soviet-style security apparatus of the Karimov era, strengthened relations with the other Central Asian countries, adopted a key role in Afghanistan’s pacification, and opened the economy to Western investment. Also, he twice visited the USA, in September 2017, when he paved the way for a series of economic agreements, and in May 2018, when he met President Trump. Although progress on human rights has been slow, Uzbekistan has clearly chosen a new direction, by which the USA is seen as a partner at least as important as Russia and China.

Second, under Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, the USA has asserted a stronger position on Central Asian affairs. In the September 2019 5+1 meeting, he condemned China’s treatment of the Uyghur minority in Xinjiang. And precisely in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, on 3 February 2020, Pompeo met Mirziyoyev and criticised China’s political and economic practices in Central Asia and beyond. In other words, at least before the pandemic, the USA seemed keener on deeper regional engagement, a position which also corresponds to President Biden’s firm global attitude towards China.

The recent and tragical events in Kazakhstan highlight the agency and bravery of Kazakhstani people, who have taken to the streets demanding better social, economic, and political conditions as well as the persistent role of Russia in guaranteeing the region’s security and stability (in the terms of the status quo). At the moment, China’s economic leverage is powerful but cannot work effectively without Russia’s security arm. The BRI, in short, also depends on Moscow, according to a somehow unusual division of labour. As far as the USA is concerned, the point now is not to promote democracy or engage with every single dimension of the region’s politics. Washington should truly return to lead by example, coordinate with the allies, prioritise key players (such as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan) and support economic development, which remains a crucial issue in a region too dependent on energy sources, minerals, and foreign investment for its material well-being.

Dr Ernesto Gallo is a Lecturer of International Relations at Regent’s University London. He has researched Central Asia, the Belt and Road Initiative, and issues of international theory and history. He has also vast teaching experience in several British institutions