While the Tigrayan rebels brace themselves for their last stand, hints of state-ordered genocide by Eritrean and Ethiopian troops emerge.

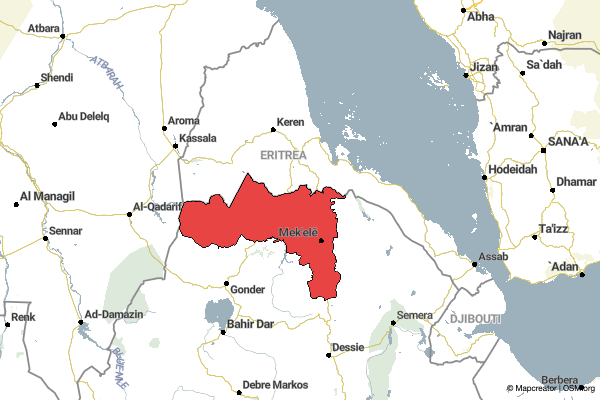

The foreshock of war pulsed through Ethiopia on the 4th November 2020, when the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) attacked a federal military base in Tigray in an attempt to steal military and artillery equipment. Now, after more than a year of fighting, Ethiopia’s military is planning to enter Tigray’s regional capital Mekelle and extirpate the Tigrayan forces.

On Friday 21st January, in an interview with state-affiliated media outlet Fana TV, General Abebaw Tadesse, Ethiopian National Defence Forces (ENDF) Deputy Army Chief, said “Mekelle and Tigray are Ethiopian territory, no one will stop us. We will go in and eliminate the enemy. There should not be any confusion about this.” This statement carries with it the power of finality, and could signal a brutal end to this devastating war.

The Tigrayan forces called their 4th November attack a pre-emptive strike against federal armies preparing to attack from a neighbouring region. However, later that same day, the Ethiopian embassy released a statement asking its citizens to “recall that in the past weeks the TPLF has been arming and organising irregular militias outside of the constitutionally mandated structure.” The article went on to say that “In addition to Federal government provocation, the TPLF through Almeda Plc – a textiles manufacturing company based in the region – have been manufacturing military outfits resembling that of the Eritrean National Defence Forces, to implicate the Eritrean government in false claims of aggression against the people of Tigray.” Whether this was an attempt by the TPLF to rally Ethiopia’s president Abiy Ahmed against the Eritrean government is unknown, but what is certain is that Eritrean forces became heavily involved in the war to come.

Arbi Harnet, more commonly known as ‘Freedom Friday’, is a liberation movement of Eritrean activists in the diaspora who seek to link acts of resistance inside Eritrea with the diaspora community. The movement has been successful in implementing a range of disruptive projects against the Eritrean regime. For example, every month, Arbi Harnet will contact hundreds, sometimes thousands of Eritrean citizens using a ‘Robo-call’ machine that allows them to make phone calls directly into Eritrea. They use these calls to encourage opposition to the regime by way of boycotting government-led commemoration events (Independence Day and Martyr’s Day), appealing to people to stay indoors on Fridays as an act of defiance, and to generate discussions about collaborative resistance.

The liberation group also established the underground newspaper ‘MeqaleH Forto’ (Echoes of Forto) in November 2013, which circulated around Asmara and surrounding areas, illuminating the Eritrean public to migrant boat accidents, human rights challenges and other topical issues. All articles in the paper were collaborative pieces, written by colleagues inside and outside of the country. More recently, in the context of the war in Tigray, Arbi Harnet received word from a high-ranking Eritrean military commander who deserted the Eritrean army and took refuge in northern Ethiopia. The chairman of the diaspora activists then interviewed the commander on a range of subjects concerning the Tigrayan war.

When asked how and when he and his military unit entered the Tigray region, he responded “We entered Tigray via Zalambessa, two days after the ENDF was attacked on the 4th November, and we entered together with those ENDF forces that fled into Eritrea. They regrouped and were rearmed and returned with us. We entered around midnight.” The war in Ethiopia then, by strict definition, is not a civil or intrastate war. From the very beginning, it has been a two-pronged, two-state attack on the Tigray region, executed by ENDF and Eritrean forces. The interviewer asks the commander to share his experiences in Tigray: “At first we were overpowered as TPLF were with their strength, both of us, and ENDF, we suffered a lot of losses. The two forces (Eritrea and ENDF) had to reorganize and at that point, they (TPFL) started to retreat. There was a lot of fighting in areas like Edaga-Hamus and that was before we reached Mekelle. There was a contingent entering through Adigirat and through the Afar region and the fight was to sandwich them in Edaga-Hamus.” He went on to say that “We (Eritrea) took a leading role in the war (compared to the ENDF) and from this, it also follows that the death toll also reflects this.”

Eritrea’s venture into this war on the side of the Ethiopian federal forces was likely a continued display of solidarity by President Isaias Afwerki towards his counterpart in Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed, following the two countries’ peace deal in 2018. For which President Abiy Ahmed was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. But chess games played at the state level rarely have the best interests of citizens at heart. The commander comments on this “It is the fact that Eritreans stand to gain nothing that has led me to abandon the whole thing. I couldn’t swallow this reality. There is never gain from conflict. I couldn’t quell my conscience and so I left. I left because the situation was bad and leaving was the only human thing left to do.”

Searching for any hint of a revolutionary spark among the Eritrean ranks, the interviewer asks “How come the leaders don’t talk among each other to bring about change in Eritrea?” To which he gets the reply “There are very few agreements in our ranks and file, we are unable to communicate and understand or trust others and so a collective decision (about change) is not possible and hence you can only make an individual decision as I did without consulting with anyone. I just decided for myself because I found the whole thing unacceptable. This was a question of conscience and my conscience would not allow me to continue so I withdrew. A collective response becomes impossible because there is a lot of mistrust and a lot of individualistic thinking. There is no one you can trust enough to talk to, even if you dare tell anyone there is no one who can respond or answer any questions so I left.” Upon further digging, specifically into whether the commander could have spoken to those soldiers under his leadership about change, the commander said “No there is no difference, it is the same, no one would hear you or accept your ideas. The misunderstanding or mistrust extends to individual levels, inside your family let alone among soldiers. Even brothers can’t discuss or agree. No one would respond (to questions of organizing for a change) even in your own family, even if you tell your own brother.”

A Niagara of wicked acts have been reported from Tigray and the surrounding regions during this war. Not least of which involved soldiers stealing civilians’ food; the commander said “At the start of the war we were hungry, there were situations where we took food from civilians, to save ourselves from dying. Later the supplies started coming for the Ethiopian soldiers, and because we were with them it was possible and it was necessary to share their provisions.” When pushed to comment on the reports of Eritrean soldiers confiscating and burning food aid, the commander replied “I can’t say much as it might be beyond me, but you see things and your conscience is disturbed as a leader. I have had complaints that lower-ranking soldiers had slaughtered sheep belonging to poor civilians. But the orders that we were given didn’t allow us to punish such actions from lower-ranking soldiers. All the instructions came from above and we could only give short punishments and do nothing more.”

On 10th August 2021, Amnesty International published a report titled ‘Ethiopia: Troops and militia rape, abduct women and girls in Tigray conflict’. The horrors detailed in the report – bravely shared by 63 female interviewees from Tigray who suffered at the hands of Ethiopian, Eritrean and other pro-government fighters from the neighbouring region of Amhara – are unimaginably grim. Even worse, there is evidence that these heinous crimes are not just random acts of violence, but a calculated and systematic attempt by the Ethiopian and Eritrean governments to damage Tigrayan women to the point where they can no longer reproduce. In other words, it is an attempt by two governments to completely eradicate an entire ethnicity.

The interviewer: “The entire world has learned about the atrocities against the people of Tigray, so do the orders come from the top?” He gets a cryptic but telling reply “Let’s not go there […] things that don’t happen don’t get talked about.” In a final attempt to concretise, the interviewer asked whether there will be evidence that orders came from the top. To which the commander replied “Correct. There is and will be evidence that orders are given from the top.”

According to Amnesty International, the scale of violations during the fourteen-month conflict in the northern regions of the country amount to war crimes. But the Ethiopian government says that the human rights group’s report is based on a “flawed methodology”.

Matthew Norman is a freelance journalist and essayist who covers African politics.